If anything can describe citizens’ feelings in Greece about the current economic situation and their future, it’s probably anxiety and, in many cases, outright pessimism. And that should not come as a surprise. The economic crisis of 2008, the pandemic, and the inflation of the past four years have contributed to the creation of an entire generation that feels trapped and without prospects.

We have here in Greece a government, which—as discussed in a previous post (“The Three Weak Arguments of the Government”)—boasts about large wage increases. This image is easily dispelled when one looks at the real figures which show that real wage increases are minimal, and especially for the lower and middle classes. In most cases there has been a reduction in real purchasing power and living standards. In other words, despite the government’s triumphalist tone, the claim that everything is going well does not match either the numbers or the reality experienced by significant social groups.

Moreover, citizens do not only look at their current situation but also tend to compare it with how things were 20 or 25 years ago. And in that comparison, the conclusions are even more disappointing: many workers feel that they will never have decent salaries or the ability to buy a home, while parents fear that their children will live under worse conditions than they did. We are living through a period where the hope people once had—that future generations would be better off than previous ones—has collapsed.

To understand why this is happening, one just needs to look at the data on wages and prices over the past two decades and assess the prospects for recovering the standard of living once enjoyed.

The longer-term view

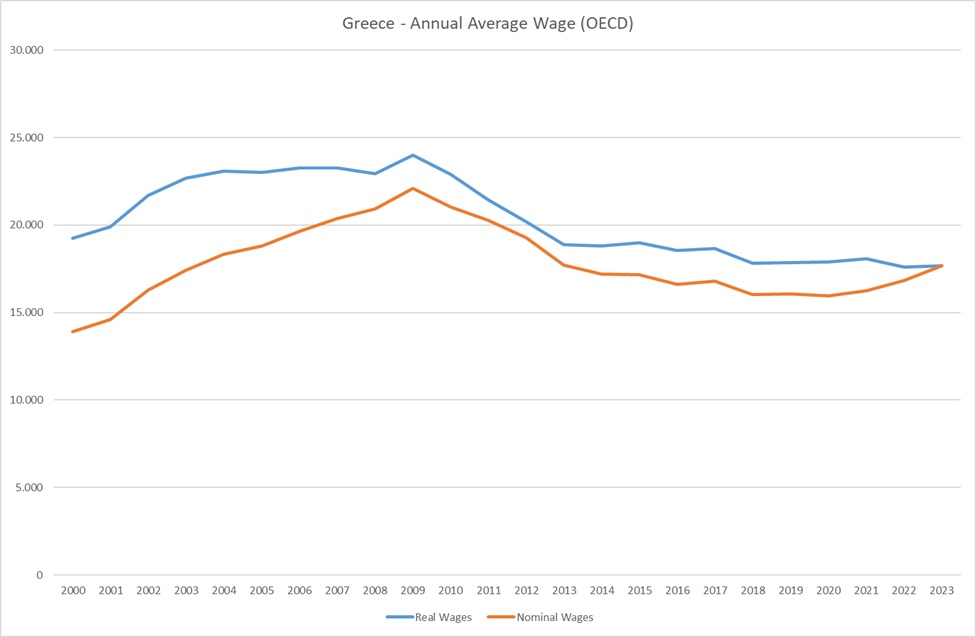

According to OECD data, the average real annual wage in Greece in 2000 (base year: 2023) was about €19,200, while the average nominal annual wage was €13,900 (around €992 per month). The corresponding numbers for 2023 were €17,700 annually, or about €1,250 per month. So, the nominal wage increased by about 27% over these 23 years, but the real wage actually decreased by about 8%.

This is clearly a result of developments in both the labor market and prices.

Starting with the labor market: pressures for more flexible labour relations and wage restraint began in the late 1990s during the convergence of center-left and center-right policies – recall the discussion around “flexicurity.” Despite pressure from the Hellenic Federation of Enterprises (SEV) for faster reforms under the Simitis and Karamanlis governments, the major assault on labour came during the structural adjustment programmes following Greece’s debt crisis, and especially during the coalition government led by Papademos. During the subsequent SYRIZA government (2015-19), some corrections were introduced to begin to redress the balance, but in 2019 the New Democracy government immediately resumed rolling back labour rights. Even today, the current government continues to push SEV’s agenda: facilitating dismissals, regulating working hours on a weekly basis, and allowing businesses to opt out of collective agreements under the flimsiest of pretexts. A recent example of this pressure for wage containment is Prime Minister Mitsotakis’ statement that Greece should bypass the EU directive mandating that 80% of workers be covered by collective agreements. Thus, his 2019 electoral promise of “many well-paid jobs” and his similar one during the 2023 election campaign to focus on wages, if elected to a second term, sound hollow. Even the OECD argues that without collective agreements, it is difficult to believe that wages will rise steadily in the future.

Now for the price side of the equation: in the last 20 years, the prices of everyday consumer goods have skyrocketed. Around 1999–2000[1], a bottle of water cost 50 drachmas (€0.15), now it’s €0.50 (+233%). A chocolate bar cost 300 drachmas (€0.88), now €2 (+127%). A cheese pie was 150 drachmas (€0.45), now €2.20 (+388%). In short, while wages rose 27%, the prices of basic goods tripled or even quadrupled.

A similar pattern can be seen in housing prices. In 2000, a 60 sq.m. apartment in Peristeri cost about €35,000 and in Pangrati about €44,000. A worker needed 35 monthly salaries to buy the former and 44 for the latter. Today, the same apartments cost about €100,000 and €150,000, respectively. Given that nominal wages rose only 27%, it now takes 79 monthly salaries to buy in Peristeri and 119 in Pangrati. In other words, for many homeownership has become an unattainable dream. Not surprisingly, the homeownership rate has dropped by about 6 percentage points in the last 20 years.

Given these facts, it’s no wonder that people feel disheartened. For many, their entire monthly income is spent on housing and basic needs, with little room for saving. A recent IME GSEVEE study showed that 60% of households said their income is not enough to last the whole month, and nearly six in ten (58.3%) said they could not handle an emergency €500 expense—or could do so only with great difficulty.

What About the Future?

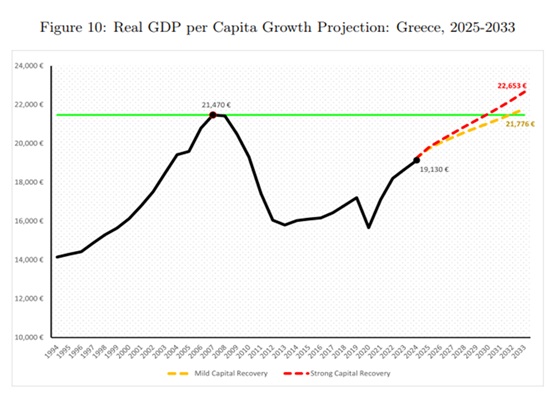

Let’s take a simple example. If we assumed that wages were to grow 5% annually (an optimistic scenario) and housing prices remained stable (highly unlikely), it would still take around 17 years for the wage-to-house price ratio to return to 2000 levels. A similar picture arises when comparing Greece’s current state to its pre-crisis condition and to the rest of Europe. In a recent study (May 2025) by Giannoulakis, Sakellaris, and Tsoukalas, it is estimated that Greece will return to its 2007 per capita GDP levels only after 2030. In other words, it will take 25 years just to recover from the crisis.

But perhaps the most critical insight comes from seeing how far Greece is from converging to a European average (regardless of whether one views the EU as a paradise!). In a favourable scenario, it would take 38 years! If we start from today’s 69% of the EU average in per capita GDP (PPP), and even assume Greece grows at twice the EU’s rate (2% vs. 1%), the European average would only be reached after 2060.

Conclusion

Decades of neoliberal dominance have not delivered their promised outcomes. The free market hasn’t led to substantial wage increases, while the prices of goods and housing have soared. This has resulted in widespread pessimism about the future, as evidenced by population decline, the brain-drain phenomenon and Greece’s extreme vulnerability to natural disasters that go with climate change. Economic stagnation will not be reversed by hoping that some time in the future the private sector will fix things. Intervention is needed to boost wages and steer the economy toward high-productivity investment for sustainable growth.

But we need to start somewhere. As long as the government doesn’t support workers’ rights and collective agreements—as even the OECD advocates—there’s no hope for real wage growth. The government’s belief that the only way to support middle and working-class incomes is through two or three jobs per person is reason enough for pessimism about the future.

[1] https://menshouse.gr/retro/92473/times-sta-ypsi-poso-kostizan-15-proionta-me-drachmi-kai-poso-me-eyro#goog_rewarded